Why Stress Hits Differently in Midlife and Why Pushing Harder Backfires

High Cortisol, Menopause, and the Stress–Hormone Cycle

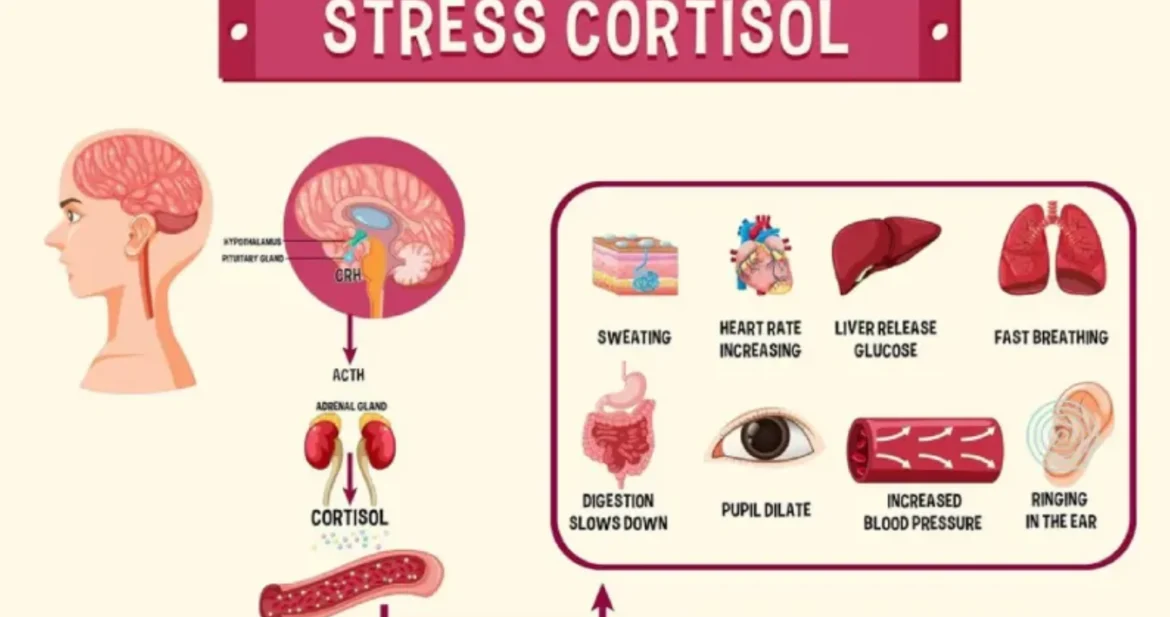

Cortisol is a vital steroid hormone that helps the body respond to stress, regulate blood sugar, manage inflammation, and support daily energy. Under healthy conditions, cortisol follows a predictable rhythm: it rises in the morning to help you wake up and gradually declines at night to support rest and repair.

Problems arise when stress becomes chronic or when hormonal shifts during perimenopause and menopause reduce the body’s ability to buffer stress. Estrogen and progesterone normally help regulate the stress response. As these hormones fluctuate and decline, the nervous system becomes more sensitive, causing cortisol to rise more easily and stay elevated longer.

Cortisol Is Often a Timing Issue, Not Just a Quantity Issue

Many women don’t have cortisol that is “high all day.” Instead, cortisol becomes dysregulated:

- Too high at night, leading to insomnia, anxiety, and night waking

- Too low in the morning, leading to fatigue, brain fog, and reliance on caffeine

This exhausted-but-wired pattern is one of the most common stress presentations in midlife.

The Cortisol Steal

Under chronic stress, the body prioritizes survival. Cortisol production pulls from pregnenolone, a foundational hormone precursor used to make estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. When stress persists, pregnenolone is diverted toward cortisol, leaving fewer resources for other hormones. This process, known as the cortisol steal, can intensify perimenopause and menopause symptoms such as fatigue, mood changes, low libido, sleep disruption, and weight gain.

Cortisol Face and Visible Stress Signals

High cortisol often shows up in the skin and face:

- Puffiness and fluid retention around the eyes

- Acne, redness, and inflammatory skin conditions

- Thinning skin, fine lines, easy bruising, and slower healing

- Jaw clenching, facial tension, and headaches

- Changes in facial fat distribution, including sagging cheeks or jowls

These changes are not simply aging. They are signs of a nervous system stuck in survival mode.

Cortisol Belly and Metabolic Impact

Chronic stress increases appetite, cravings, and insulin resistance while signaling the body to store fat, particularly in the abdominal region. Abdominal fat is highly sensitive to cortisol, which is why the midsection often becomes resistant to change during perimenopause and menopause, even with consistent nutrition and exercise.

High cortisol also contributes to muscle breakdown, slower recovery, bone loss risk, blood sugar imbalance, and persistent fatigue.

This is not a lack of willpower. It is a physiological stress response.

Why Lowering Cortisol Isn’t About Doing Less, but Doing Differently

Cortisol itself is not the enemy. Acute stress is necessary and protective. The problem arises when stress is constant, unresolved, and unsupported.

Blood Sugar and Cortisol

Blood sugar instability is one of the fastest ways to spike cortisol. Skipping meals, under-eating protein, restricting carbohydrates, or over-exercising can all signal danger to the body. When blood sugar drops, cortisol rises to compensate. Over time, this creates a loop of fatigue, cravings, anxiety, and stubborn weight gain.

Exercise as Stress

Movement is essential, but not all exercise lowers cortisol. High-intensity workouts, excessive cardio, or training without adequate recovery can raise cortisol further, especially in midlife. Many women unknowingly stress their nervous systems through “healthy” habits that are no longer supportive.

Gentle strength training, walking, mobility work, and restorative movements often improve cortisol balance far more effectively than pushing harder.

Cortisol and the Immune System

Chronically elevated cortisol suppresses immune function and increases inflammation over time. This can show up as frequent illness, slow healing, autoimmune flares, skin conditions, and increased sensitivity to stressors that were once manageable.

This Is Not a Personal Failure

High cortisol is not caused by weakness, laziness, or lack of discipline. It is the result of long-term stress, stored tension, hormonal transitions, and a nervous system that has learned to stay alert for too long.

The Path Forward: Regulation, Not Force

Lowering cortisol begins with sending consistent signals of safety to the nervous system:

- Regular meals with adequate protein and nourishment

- Restorative sleep and circadian rhythm support

- Gentle, supportive movement

- Breathwork and somatic practices

- Nervous system regulation before pushing for change

When cortisol comes back into rhythm, the body can redirect energy toward hormone balance, metabolism, repair, and resilience.

Key Takeaway

Healing high cortisol is not about doing more. It’s about doing what supports your nervous system in this phase of life. When stress hormones soften, the body remembers how to heal.

Cortisol Support Checklist

Use this checklist to gently identify what may be raising cortisol and what helps bring it back into balance. This is not about perfection; it’s about awareness.

Common Cortisol Raisers

- Skipping meals or under-eating, especially protein

- Long gaps between meals leading to blood sugar crashes

- Excess caffeine, especially on an empty stomach

- Poor or inconsistent sleep

- Late-night screen time or bright lights

- High-intensity or long-duration exercise without recovery

- Over-scheduling and lack of rest days

- Chronic emotional stress or unresolved tension

- Holding your breath, shallow breathing, jaw clenching (check in, is your tongue plastered to the roof of your mouth?)

- Unprocessed trauma!

Cortisol-Lowering Supports

- Eating regular meals with protein, fiber, and healthy fats

- Starting the day with nourishment before caffeine

- Gentle strength training and walking

- Consistent sleep and wake times

- Morning light exposure

- Breathwork and slow exhalations

- Somatic movement and nervous system regulation

- Creating daily moments of safety and rest

- Compassionate self-talk and realistic expectations

0